Image by CoPilot

Image by CoPilot

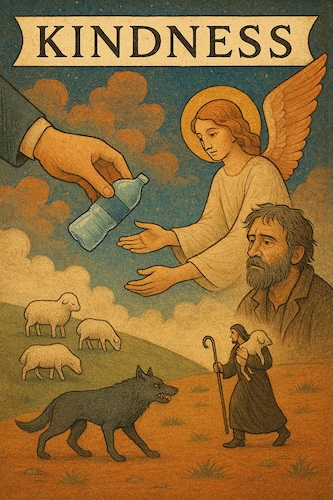

Kindness, Superagency, and the Mind of God

"What is, has been already, and what is to be has already been; and God seeks what has been driven away." —Ecclesiastes 3:15

In Cliff, New Mexico, where the stars burn with ancient light and metaphors come easy, I've spent the past season reflecting on three interwoven truths: kindness, agency, and the mind of God. What began as separate essays has revealed itself to be a single mosaic—one shaped not by certainty, but by mercy.

It began with my better half, Donna. Her quiet act of grace—unnoticed by most, unforgettable to me—shattered my assumptions and revealed the gap between sentimentality and true mercy. Kindness, I learned, is not a feeling but a force. It interrupts, humbles, and heals. It is the divine logic that rewrites our scripts and invites us to live differently. In a world that rewards cleverness, kindness is often dismissed as naïve. But I've come to see it as the most radical form of agency—a choice to extend grace where none is required. It is the heartbeat of the divine.

From kindness, I turned to agency—not the brute force of will, but the subtle flicker of moral freedom. In quantum physics, particles behave probabilistically, not deterministically. They oscillate, exist in superposition, and collapse only when observed. This uncertainty mirrors our moral lives: we are not locked into fate but invited into freedom.

But agency alone is not enough. We needed a term for the kind of choice that transcends instinct, habit, and even self-interest. That's where superagency emerged—not as a scientific term, but as a theological metaphor drawn from quantum behavior. Superagency is the capacity to choose mercy when determinism might excuse cruelty. It is the theological twin of quantum indeterminacy.

Just as particles defy prediction, so too can we defy our worst impulses. We are not merely acted upon—we act. And more than that, we re-act in ways that break the expected pattern. Superagency is not just freedom—it's redemptive freedom. It's the moment when a person, like a particle, collapses into grace rather than grievance.

In this light, every act of kindness becomes a quantum event—a collapse into mercy that could have gone another way. And every such collapse reshapes the moral field around it, like entangled particles influencing one another across space and time.

Recently, I stumbled upon an article about time crystals—a material that "bends time" by repeating patterns without energy loss. Physicists now suggest that time may be emergent, not fundamental—a rhythm, not a river. This discovery echoed something I'd long suspected: that God's mind is not bound by chronology, but dances in recurrence. It is like God's paintbrush, oscillating back and forth through past, present, and future, creating a mosaic that illustrates the entirety of the picture. Time crystals don't merely repeat—they remember. They embody a rhythm that persists even in the absence of energy. What a metaphor for divine mercy: a force that does not tire, does not fade, but pulses eternally.

Scripture speaks of a God who "seeks what has been driven away." Not a linear deity, but a fractal one—revisiting, redeeming, restoring. Recent geological studies reveal that Earth's deep history follows a multifractal rhythm, with mass extinctions and evolutionary leaps clustering in patterned intervals. What seemed like chaos obeys a deeper order. Perhaps mercy is that order. Perhaps divine intelligence is not a distant architect, but an artist painting with an oscillating brush. And perhaps superagency is the human echo of that divine rhythm—a moral time crystal, pulsing with grace in a world that often forgets how to forgive.

This mosaic—kindness, superagency, and the mind of God—is not a doctrine, but a testimony. It's the story of a mechanic who writes, a seeker who stumbles, and a man who learned that mercy is not weakness, but method.

Beneath this reflection lies a quiet scaffolding: the idea that mercy is not merely a virtue but a kind of metaphysical agency—what I've called superagency. It's the notion that kindness, freely chosen, participates in a deeper rhythm woven into creation itself. Just as quantum indeterminacy allows for possibility rather than inevitability, so too does mercy interrupt the expected and invite the divine. If time crystals suggest recurrence without decay, then perhaps mercy is their moral analogue—grace returning again and again, not by law, but by love. This essay, then, is not only a meditation; it is a hypothesis in disguise—a theology of rhythm and response.

"I desired mercy, and not sacrifice; and the knowledge of God more than burnt offerings" (Hosea 6:6).

Perhaps mercy is not the exception to the rule—but the rhythm by which the rule was written. And if so, then every act of kindness is not merely good—it is participatory. It is a note struck in the music of God's mind, echoing through time not as sentiment, but as structure.

This reflection is the first movement in a larger composition—an unfolding trilogy of thought: Kindness, Superagency, and The Mind of God. Each seeks to trace the contours of mercy, choice, and divine rhythm. Together, they ask not only what is true, but what is good and beautiful—and whether truth itself might be a kind of mercy.

If these reflections prompt even one act of grace, one moment of humility, one deeper question about the nature of time and the mercy that redeems it—then they've served their purpose. May your own journey be lit by grace. And may you find, as I have, that the stars above Cliff are not the only things that shine.