By Ruben Leyva, Gila Apache

The Denver Public Library Digital Collections caption reads, “Apaches Fel-ay-tay Yuma scout, San Carlos.” In another, more obscure photograph, perhaps the same individual stands wrapped in a patterned blanket, his face lowered and half-hidden among a group of Native Americans on the steps of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This individual, the label states, is "Francisco, Indian Name – 'Hollow Loud'" and is among a group of Navajos. But he was neither Yuma nor Navajo. His baptismal name was Francisco de Jesús Leyva (pronounced Lay-vah). He was born a member of the Warm Springs Apache and married and started a family near the Gila River.

The Denver Public Library Digital Collections caption reads, “Apaches Fel-ay-tay Yuma scout, San Carlos.” In another, more obscure photograph, perhaps the same individual stands wrapped in a patterned blanket, his face lowered and half-hidden among a group of Native Americans on the steps of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This individual, the label states, is "Francisco, Indian Name – 'Hollow Loud'" and is among a group of Navajos. But he was neither Yuma nor Navajo. His baptismal name was Francisco de Jesús Leyva (pronounced Lay-vah). He was born a member of the Warm Springs Apache and married and started a family near the Gila River.

Known to his family as Jesús or Apache Frank, a nickname given to him by English speakers, he lived through some of the most brutal chapters in Apache history. His story is not one of confusion but of calculation. Captured, renamed, misfiled, reclassified, and assumed dead on at least two occasions, Frank's life story unfolds as a ledger of imposed identities and acts of quiet resistance. Some records and oral history place him with the Yuma—an affiliation later echoed by Fort Sill historian Gillett Griswold, who documents Frank's temporary enrollment with both the Yuma and Mescalero Apache. These overlapping identities, often shaped by military classification, survival, marriage, and parentage, frame the puzzle that this editorial attempts to piece together. What follows is not a definitive identification, but a careful weaving of oral testimony, archival records, and photographic clues that bring us closer to the truth of a man who moved between names.

Oral history and genealogy support that he was born before 1850 to Norberta (Ishnoh'n) Leyva, a Warm Springs Apache matriarch. Frank was raised during a time of intense conflict across the greater Southwest landscapes. His mother's father, Josécito (Naashchéézoo) Leyva, was among those who negotiated with New Mexico Territorial Governor William Carr Lane. His Navajo stepfather, Hosteen (Has-te-en), raised him alongside his brother, Eskinzon, also known by his English nickname, Chiricahua Jim. The term 'Chiricahua' was dangerous for a Warm Springs Apache at that time. Frank and his full brother, José Albino, avoided deportation to St. Augustine, Florida, by never boarding the train. Unfortunately, their mother and younger brother, Chiricahua Jim, were not as lucky.

Years earlier, Frank was with Geronimo's band, which attempted to join Victorio's reservation at Ojo Caliente rather than go to San Carlos. Frank was also visiting his family. Indian Agent Clum and his San Carlos Apache police forcibly took them west to the San Carlos Agency in 1877, where they had been assigned by Indian Affairs, but had refused to stay. Apaches Loco and Victorio, along with their Warm Springs bands, including Frank's parents, Hosteen and Ishnoh'n, were also forcibly relocated, even though they were not included in Clum's orders. After a breakout four months later and a brief stay at Fort Wingate, they were allowed to return temporarily to Warm Springs, at Cañada Alamosa, until the fall of 1878. They were sent back to San Carlos feeling betrayed by the U.S. Meanwhile, Victorio took his followers into the Black Range rather than wait to be deported again.

To clarify the sequence: After being forcibly marched to San Carlos in 1877, Frank and his family were briefly allowed to return to Warm Springs later that year but were sent back again by the fall of 1878. By October 1879, Lieutenant James A. Maney recruited Frank as an Apache Scout. He reenlisted in early 1880 and likely participated in key campaigns at Hembrillo Canyon (April 1880) and Palomas Creek (May 1880).. In April 1882, he may have been present during the Stein's Peak–Horseshoe Canyon battle, after which scouts were presumed dead. Later that year, in October 1882, he reemerged at the Carlisle Indian School under the name Francisco—another chapter in a chronology shaped by capture, reclassification, and survival.

My interpretation is rooted in Allan Radbourne's research notes, which illuminate additional pieces of the puzzle regarding Apache Frank and his stepfather, Hosteen. Volume 152 of the Register of Enlistments of Indian Scouts reveals that Lieutenant Maney recruited the first twenty-four Arizona Apaches in October 1879. Maney reenlisted Frank and other Apaches on January 1, 1880, forming Company "A," and they were later discharged. On March 20, he reenlisted with Maney, and he was joined by Hosteen and others, totaling 63 Scouts in service, suggesting that 24 may have reenlisted alongside the additional 36 men. No details are available on the March 20 reenlistments concerning age, occupation, or description, except for height. Among them are Frank and his stepfather Hosteen, listed as "F. 384 Frank (5-4") and H. 287 Hosteen (5-10")."

Not long after he arrived at San Carlos in 1878, it appears that Frank became entangled in the web of U.S. Indian policy, which utilized Apache Scouts (as established by the Army Reorganization Act of 1866), and became part of an effort to track Victorio's Warm Springs Apaches. The Scouts enlisted for a brief period of three or six months before being required to reenlist for another term. Reference archivist at National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Trevor Plante, writes, "The Indian Scout enlistment paper index can be challenging to use in some cases. The scout can be listed under the Native American phonetic spelling of his name (with no translation) or under the English translation of his name." Hosteen may have been killed in battle, as Griswold's research states that Hosteen died before 1886 and did not accompany his wife, Ishnoh'n, to Florida.

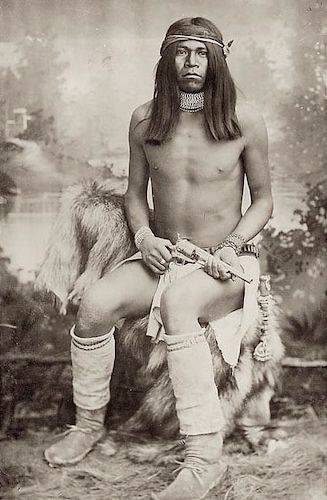

Evidence suggests that a man photographed in 1885 by Baker & Johnston was Frank. Baker & Johnston's list names him Felaytay and describes him as Yuma, San Carlos Apache. The photo shows a composed individual, not a caricature of a "savage," but a poised man asserting his presence. When compared to the Carlisle image taken a few years before, striking similarities emerge.. Both individuals wear their hair parted down the middle, a headscarf tied on the left, and share a similar facial structure, particularly around the jaw and mouth. These visual parallels, while not definitive, strengthen the possibility that both photographs capture Frank Leyva under different names and conditions. At Carlisle, he was recorded as 5 feet 5 inches tall. A military scout or mule packer listed at 5 feet 4 inches, photographed during a campaign, could easily have been him. Misidentification was common: Apache, Yuma, and Yavapai men were frequently mislabeled in military records. The name "Felaytay" may have been a scrambled phonetic rendering of 'Frank Leyva.'

In 1882, the peaceful leader Loco, driven from San Carlos by the return of Apache bands led by Geronimo, fled with women and children toward Mexico. In response to the breakout, Lieutenant Colonel George A. Forsyth dispatched Lieutenant David N. McDonald with six Indian scouts to reconnoiter Horseshoe Canyon. McDonald later recalled seeing "the legendary Yuma Bill fall," but Forsyth's official report first listed two Indian scouts dead and only "blood on the ground suggesting more." Historian Robert M. Utley notes that the Apaches themselves admitted to just one fatality and that Forsyth, "curiously unconvinced," broke off the pursuit rather than confirm the bodies. The four names that eventually made the rolls—Yuma Bill, Kaloh Vichajo, Panocha, and Ceguania—were, therefore, more an inference than a certainty, which helps explain why their sacrifice lingers only faintly in the record.

While Robert A. Miles' book documents Yuma Bill's death during the 1882 Stein's Peak battle, he goes a step further, matching Yuma Bill to the Apache name Felaytay, but offers no citation to support this as an identification. The photo Miles proposes was taken around three years later. While Felaytay may have been present, the historical record provides less certainty than Miles explains. Just as plausibly, some men survived—perhaps wounded, perhaps disillusioned—and quietly withdrew from the scene. The U.S. military declared breakouts as hostile. Within weeks, nearly a hundred Apaches—women, children, and scouts—were reported killed in the running fights that climaxed with Mexican troops in Mexico.

Given his enlistment with Maney a couple of years earlier, Frank would have served as an Apache Scout in the Victorio Campaign, which included the fights at Hembrillo Canyon and Palomas Creek. Alicia Delgadillo's research places Chiricahua Jim with Kaahteney's band, which would have pitted Frank and his stepfather against other Warm Springs Apaches, such as Kaahteney (Jacob), Nana, and Victorio, in those battles. However, this was not the end of Frank's story.

Griswold states that Mexicans captured Frank, and then Anglos from Arizona took him from the Mexicans. The Anglos sent him to an Indian School in Pennsylvania, where he received his education. Archival records indicate that he was identified as Francisco at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and listed as Navajo in October 1882. His enrollment card listed the address as "Hostee del-a bishahegay," which was likely his stepfather's name, as a family member's name was often used as the address. Although usually assumed to have been part of the larger group of Warm Springs Apache sent east in 1884—including Parker West—Frank arrived earlier and independently. His enrollment in October 1882 places him outside that delegation, reinforcing the idea that he was misclassified, misfiled, and perhaps deliberately obscured.

Two rare Carlisle photographs from this period, taken moments apart, show a male wrapped in a woven blanket, possibly bare-chested. His head was lowered, blending into a group of traditionally dressed Navajos on the school steps. This may have been a moment of shame—or a tactical withdrawal from visibility.

He left Carlisle less than a year later, on July 10, 1883. Official records noted him as "dead." But it was a second vanishing—an act of refusal. Like many students who walked away, Frank returned to the Southwest via New Orleans. The 1885 Mescalero Census documents him as married with four children listed. He traveled farther south to Chihuahua, where Apache families like his had long sought refuge. Fort Sill historian Gillett Griswold notes: "He was enrolled with the Yuma, then the Mescalero Apache. He was never enrolled with the Fort Sills."

Griswold’s research strengthens the possibility that the 1885 Baker & Johnston photograph labeled “Felaytay, Yuma Scout” depicts him. The Yuma Tribe was not from the area; they were forcibly relocated to the San Carlos reservation in 1875, more than 180 miles from their home to the west. Griswold's research strengthens the possibility that the 1881 Baker & Johnston photograph labeled "Felaytay, Yuma Scout" depicts him. While the name Felaytay may represent a phonetic rendering or alias of Frank Leyva, the picture and Griswold's account together suggest a layered identity shaped by necessity and survival.

His life disrupts the neat categories so often imposed on Apache identity. He was a scout and a resister, a school enrollee and an escapee, an Apache who once passed as Navajo, possibly photographed as Yuma. His story is not one of confusion but of calculation. He lived within systems designed to erase him, and yet he outlived those systems.

Today, when we look at those two photographs—the confident warrior with the revolver and the shrouded figure in Carlisle—we are not seeing contradictions. We are witnessing survival. Francisco de Jesús Leyva was not erased. He was renamed, refiled, and recorded incorrectly. However, in the oral traditions of the Warm Springs Apache, the Chih Ndee (Red Paint People), and the living memories of his descendants, his voice still echoes. Returning to the Sierra Madre—after he departed from Carlisle or time spent among other Apache survivors—Frank may have sought out fellow kin and news of the exiled bands, including Loco's people.

His mother, a POW at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, was still alive when he found her there as an older man. His journey ultimately brought him back to her before 1909, writes Alicia Delgadillo in *From Fort Marion to Fort Sill*. Eve Ball's *Indeh* identifies him as "Francisco." While at Fort Sill, he met Asa Daklugie, son of Lino (Juh) Leyva. Asa did not recognize him at first—he had lost much of his family in his youth. However, the older man recounted being captured and taken to Baja California and described the fate of Asa Daklugie's brothers. Frank later told Asa that he had tried to reach them after returning to the Sierra Madre, but it was too late. The brothers had already been tortured and were to be taken to the City of Chihuahua.

As confirmed in Edwin R. Sweeney's *From Cochise to Geronimo*, Delzhinne and Daklegon were captured in December 1885 by Terrazas' scouts near Casas Grandes while attempting to reconnect with Mangas (son of Mangas Coloradas). Federal soldiers later transferred them to Mexico City, where they disappeared from the historical record, never to return. Their disappearance mirrored the experience of many Apache captives—spirited away across borders and bureaucracies, lost to their families but not to memory.

This account from Ball cross-references with Fort Sill historian Gillett Griswold, who wrote about Frank's capture and identification as "Yuma," which likely arose from his time enlisted as a scout at San Carlos, or as a captive in Baja California, or both. The Baja California–Arizona border is the ancestral home of the Fort Yuma-Quechan Tribe.

His was the kind of life that complicates history and corrects it.

Frank's life invites comparison to a Warm Springs Apache named Massai. According to the late Chiricahua POW Jason Betzinez, Massai served as an Apache Scout against Victorio. Later in 1882, he deserted his military unit upon receiving news that Geronimo had forced Loco and his band from San Carlos, as Massai was concerned about his wife's well-being. He was living at San Carlos at the time of Geronimo's surrender in 1886 and was sent east with the other Chiricahuas at San Carlos from Hollbrook, Arizona. He managed to escape the POW train in 1886 near St. Louis and returned on foot to the Southwest. Massai's story, mythologized over generations, has come to symbolize warrior defiance and a return against all odds. While Massai is considered the first, Frank pioneered his historic return three years earlier.

He was not listed among the POWs. He was not sent to Fort Marion or Mount Vernon. Yet, like Massai, Frank refused to be erased. He escaped invisibly—by stepping sideways through the cracks of federal classification, by letting them believe he was dead, by walking back to his people without announcement or ceremony.

Where Massai's tale fits a familiar template of heroic return, Frank's is more "elusive," according to Alicia Delgadillo. His resistance was not only physical, but also spiritual. Through exile and return, scouting and survival, schooling and escape, he kept the thread of memory alive. His movement across San Carlos, Carlisle, Mescalero, Baja California, and the Sierra Madre was not just geographic—it was ceremonial. He moved like those who run between camps carrying embers and prayers.

Some might find quiet significance in his baptismal name—Francisco de Jesús. Like Jesus of Nazareth, he was declared dead yet lived. Declared dead once more, he remains remembered. In Apache Frank's story, we witness not a resurrection in the Christian sense, but a return—a continuity of spirit through displacement, disappearance, and reappearance. Historical evidence, in the form of records and photographs, demonstrates that he lived and navigated systems that sought to suppress him. He emerged, not unchanged, but not destroyed or diminished. His was a resurrection of identity, carried not in gospel but in the memory of those who knew his name.

In 1941, his death was reported again—this time accurately—in San Francisco de Conchos, Chihuahua. His sons, Roman and Tomás, confirmed it. Frank, like many of his Apache brethren, had found refuge in Mexico.

Frank and Massai's journey accentuated the U.S. government's shoddy treatment of its Apache Scouts. But Frank's story, grounded in survival and memory, honors those who endured in silence and the shadows. In this way, he becomes a different kind of hero—one who reshapes our understanding of resistance. Not all heroes carry the title.